Jewish Saharans Singing To Birth

A Project of Dr. Vanessa Paloma Elbaz based on oral history interviews of Mme. Sultana Azeroual in Casablanca 2015 - 2016. Full interviews are held in KHOYA: Jewish Morocco Sound Archive. If you have a story to share, please upload it unto our portal at the Share your Story tab.

Ya Lalla: Oh Queen

I was born in the Moroccan Sahara and live surrounded by family, friends, and song.

We, the women , speak in blessings and prayers in Judeo-Arabic wielding the power of words for our loved ones. With our songs, comes our power – to bless or to curse.

There are songs for happiness, songs for marriage, songs for birthing, even a song for when a woman’s water breaks during labor. All our feelings, worries and joys are voiced through song .

Song for Water Breaking in Labor

We have one day left

If Gd wills it, oh dear Gd!

Her water breaks

If Gd wills it, oh dear Gd!

Make the infant come out today

If Gd wills it, oh dear Gd!

Today’s the eve of Friday

If Gd wills it, oh dear Gd!

Make the infant come out

It’s its day today

If Gd wills it, oh dear Gd!

Bekkat Lina ghir Lila

Inchallah yarebi

Kherejou lweliyed Lila

Inchallah yarebi

Lila lilet jamâa

Inchallah yarebi

Jebdou lweliyed Lila

Inchallah yarebi

I married incredibly young and went to live in my husband’s town, Boudenib, close to Rissani, in the Tafilalet region, the largest Saharan oasis in Morocco.

This is the region where the Royal Family’s Hijazi ancestors moved to in the 12th or 13th century as well as the region that has birthed many important Tsaddikim , such as the Baba Sale, Rabbi Israel Abuhatzera. The Tafilalet is a holy land, imbued with holiness and royal lineage. Women often sing to the Tsaddik Rabbi Meir Baal HaNess from the 2nd century, the Maker of Miracles whose wife, Bruria was a scholar and is one of the only women named in the Talmud.

Rabbi Meir Baal HaNess Song

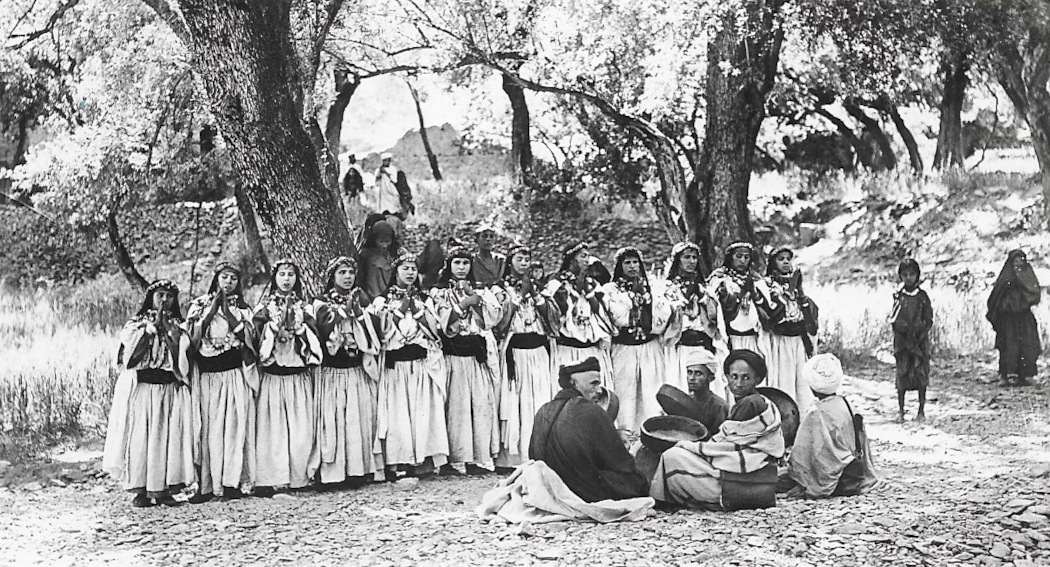

When I was a young mother, my friends and I would get together in the central courtyard of our houses to sing while we cooked, kneaded bread, did chores, and watched our children. Today everyone lives spread out and we only sing when we gather on special occasions such as weddings, births and Bar Mitzvahs.

My children and grandchildren live in Casablanca, Paris, New York and Israel. None of them know these songs anymore.

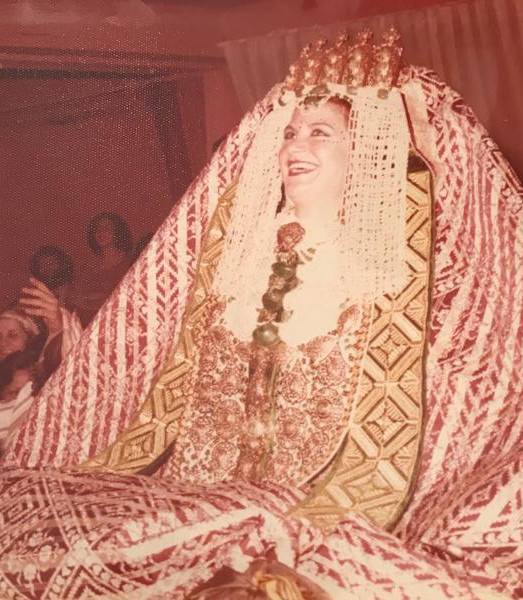

When they get married, we have an extravagant Henna celebration , to protect them from the evil eye and to sing blessings into them and into their future children. We know that the power of our voices travels down through the generations. For most brides, the Henna is more important than the wedding with the white dress.

This is the powerful night when the women plant their blessing into the couple for fertility , success, and happiness.

We sing, we dance, we do yu yus and we bless the whole family, generations into the future.

Women would gather for tea and sweets and sing to the mother-to-be, blessing her to have a healthy child.

At the beginning of the ninth month of pregnancy, when we lived in the Tafilalet, women would gather for tea and sweets and sing to the mother-to-be to have an easy delivery, to have many celebrations .

We would gather around the mother-to-be every day to help usher in the new life that was coming. These were moments to laugh and celebrate the new baby, and her as a mother. Some songs joked about wanting a boy over a girl, because the mother’s status was higher if she had boys.

Song for a Boy over a Girl

If you tell me it’s a boy

I will give you twice this song!

But if you tell me it’s a girl

With a stick, I’ll get you out of my house!

O blessed fortunate woman!

Announce the good news, say it’s a boy that is on the way!

But if you tell me it’s a girl

With a stick, I’ll get you out of my house!

If you tell me it’s a boy

I will give you a pair of earrings!

But if you tell me it’s a girl

By the stick, you’ll get hit on the head!

And here I am with your little boy

He found food and drink

Pillows and a bed

The bed is made of silk

The candle is shining in my room

Accompanied by the tray

Dear lady, here it comes, what is happening

Poor me, oh my lady, oh mother!

What a pity, increase my enjoyment!

God will come to save us!

īla gulti l-i ṣabe

năˁṭe-k zūza huwwāre

w-ila gūlti l-i ṭəfla

b-lă-ˁmūd txərzi mən ḍāṛ-i

ya rəbḥa ya məṛbōḥa

bəssri l-i b-ūlīid ixlāq

w-ila gūlti l-i ṭəfla

b-lă-ˁmūd txərzi mən ḍāṛ-i

w-ila gulti l-i ṣabe

năˁṭe-k zūza məl-lə-xṛāṣ

w-ila gūlti l-i ṭəfla

lă-ˁmūd tāxəd ˁăla ṛ-ṛāṣ

w-ana băˁda măˁa ulīid-ək

ṣāb l-mākla u-s-srāb

u-l-xəddīyāt u-l-fṛās

u-l-fṛās d-l-ḥṛēṛ

u-s-səmˁa gādya f-bīt-i

u-ṣ-ṣēnīya mṛāfəg-a

A lalla hāili u-ma l-i

ˀăḥ yāna lalla u-mm-i

ˀăḥyana kətru ˁzūb-i

dāba ṛəbb-i ifəkk-na)_

Today, many women sing those songs less, because we want to have girls as much as boys.

We, the older women, know the fear and pain of childbirth. Childbirth was a dangerous moment in the life of both the mother and the child. When we left the bled (homeland) and moved to Meknes, we continued singing, as well as when we moved to Casablanca in the 1990s. I still sing these songs to my daughters and grandchildren who live in Paris, Israel and New York, but many do not know how to sing them anymore.

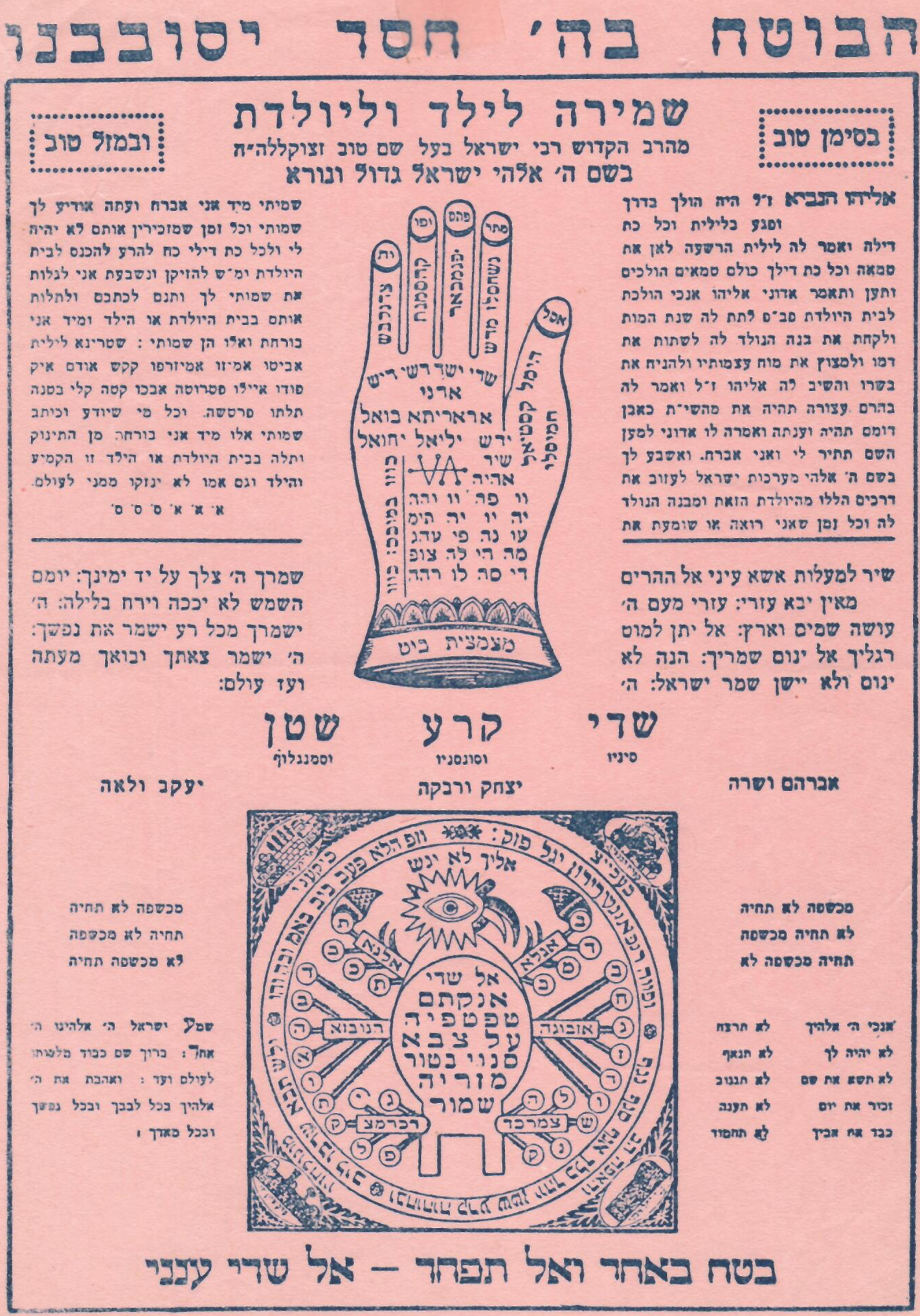

The first 40 days after birth are the most perilous for mother and child .

Many of our century-old traditions were meant to protect the mother’s and baby’s health, before science took over childbirth and made it a medical procedure.

Mother and child stayed in their room, protected from germs, and the mother rested and was taken care of as she healed. If the baby was a boy, the week before the brit (circumcision) the men would come every night to perform the tahdid sword ceremony.

The word Tahdid comes from hdid, metal, in Arabic, bringing in technologies of metallurgy to protection rituals. The women used to hold the mother and baby ‘hostage’ in the room and barter jokingly with the men who were knocking at the door and begging to come in. Joking negotiations back and forth in Judeo-Arabic were meant to make everyone laugh and ensure that everyone knew where the real power was! Once allowed into the mother’s room, the men sang liturgical poetry in Judeo-Arabic and Hebrew, lightly tapped ritual swords against the walls of the four corners of the room, on the baby’s crib and on the four cardinal points, all the places where the evil spirits are said to hide. They then continued singing mystical poems and murmuring prayers in Hebrew and the women finished with loud yuyus of celebration. Afterwards there is a feast for everyone gathered. This Tahdid, from July 2013, was led by the paytan Jacob Wizman, a student of the famous Rabbi David Bouzaglo. Filmed in Casablanca by Ron Duncan Hart.

When the French Protectorate began in Morocco, childbirth became medical and slowly our voices were silenced.

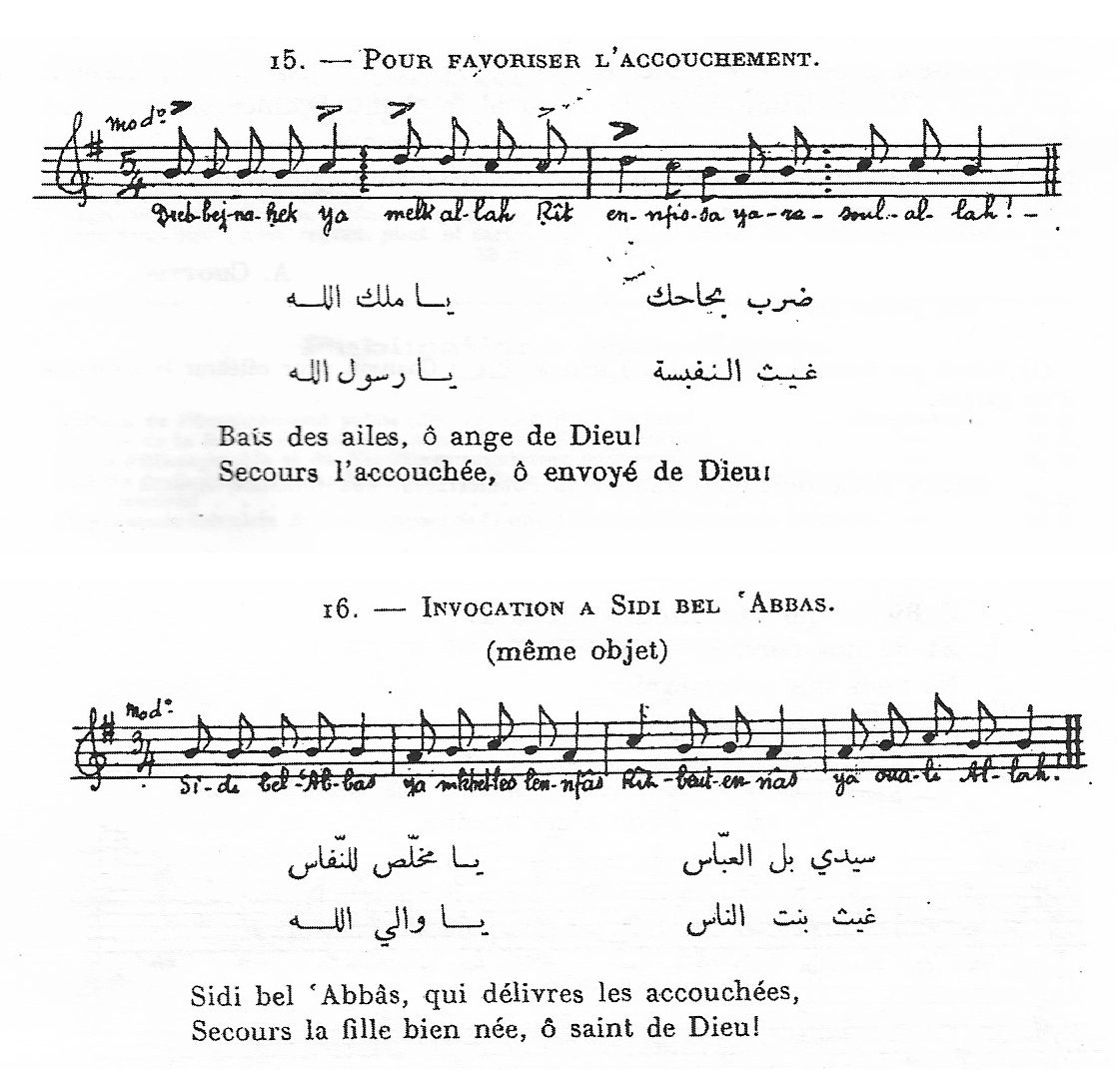

We began having our babies in hospitals and staying there for a month of recouperation, cut off from our community. Some of the dangers were taken away, but so were many of our traditions . French scholars said our music, which is rhythmic and cyclical, was like the Amazigh areas, less controlled by the central government which they called bled el siba. The musicologist Alexis Chottin declared it primitive, uncultured, rural and connected to nature. The French preferred Andalusian melodies which represented bled el mahkzan, the lands controlled by the Sultan, and were according to Chottin, urban, melodic, civilized and refined. Our children were educated in French schools, we gained access into the Western world’s economic opportunities, but lost many of our own ancestral traditions.

We however, continued singing through our migrations and even in exile.

Thousands of Moroccans do not know these traditions anymore and many feel disconnected from the depth of their millenary traditions. This cultural deracination often breeds depression and anxiety leading young people to feel isolated and incompetent. I know that young women in the big metropoles of Paris, London and New York might want to feel the enveloping circle of these powerful voices that can accompany them in their mothering .

Women in the Maghreb may reconnect to the soundscape of past women’s celebration of the power of bringing new lives into the world and restitch the broken chain of women’s singing to birth.

We hope this online resource will inspire you to reclaim and revive these powerful traditions.

Further Reading